Using original interviews and home movies shot between 1993 and 2005, a filmmaker works to reclaim his heritage by exploring why his parents crossed the Mexican-American border and what was lost in raising their family on the other side.

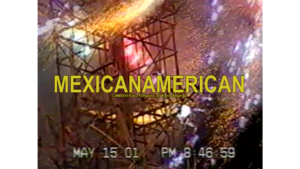

MEXICANAMERICAN

$50,000.00

Goal-

$0.00

Raised -

176

Days to go

The white noise of analog video static fades in before transforming into the white noise of waves crashing against Colima, Mexico’s Pacific coastline on Tuesday, October 18, 1993. My parents, Eduardo “Lalo” Sánchez and Evelia “Beby” Suárez de Sánchez, are celebrating their honeymoon just two days after their wedding took place in the rural outskirts of Guadalajara, Jalisco.

The VHS footage documenting this trip lets us see each of them through the other’s eyes as they take turns operating the camcorder. The infectious joy bursting from their grins evinces the eagerness with which they embarked on the rest of their lives together. That joy is abstracted into psychedelic sparks of color erupting from Mexican firework castles and intercut with shots of my dad on the beach attempting to build sandcastles. Again and again, the ocean tide flattens his crude mounds of sand, but every time it does, he simply takes another step forward and tries again.

“This is the story…” reads the pixelated on-screen text of the VHS tape, “of how Lalo and Beby built their home together… and what it cost.”

Twenty-seven years later, my parents sit on the deck behind their beautiful suburban home in Oregon as they adjust the camera on their Zoom call with me. This largely biographical interview, which I conducted at the height of COVID-19 from the opposite end of the U.S., is the first of three that occurred across three years. These interviews (along with a fourth, with my brother Edgar) form the film’s core, brought to life by dozens of the home videos my parents sent over the border between 1993 and 2005 as a means of “visiting” the families they could not physically be with before naturalizing as U.S. citizens.

My parents recount how they met as 16-year-olds at a dance where my mom was elected beauty queen of her hometown’s Mexican Independence Day festival in 1985. Although they instantly developed feelings for each other, my mom had a boyfriend, and my dad was about to cross the border as a seasonal laborer just six months later.

Crossing the border at 16 was a rite of passage akin to going to college. My dad, who dropped out of school at 12, idolized the young men of his poor, subsistence-farming community who, after a mere few months, returned from the U.S. with pickup trucks, blue jeans, and enough money to marry and build houses back home. He saw the U.S. as the place where one accomplished all the good there was to accomplish.

From my mom’s vantage point, however, the U.S. was a malignant force that tore families apart. Having only seen the border separate parents from their sons and wives from their husbands, she swore never to leave her own family behind.

That was, until my dad returned for her.

After my mom married my dad, their wedding, honeymoon, and the construction of their house drained him of the savings he had made working up north. My mom, having seen how much harder my dad worked in Mexico for so much less, agreed to a part-time living arrangement: six months in each country at a time. But then she became pregnant with me, and suddenly all she could consider was how to provide me with a better life than hers. That was when she realized—through the most difficult decision of her life—that she had to leave Mexico for good.

What followed was how my parents dealt not just with the literal distance from their families abroad, but the inner distance that formed between them and their three sons—Edgar, Eben, and me. Despite the devotion and pride with which my parents upheld the culture, language, and values of their origins, we gravitated toward the media we consumed and what surrounded us at school. We assimilated so thoroughly that we rejected Catholicism, our facility with Spanish fell away, and our new, unfamiliar life experiences alienated us from our parents.

That alienation worsened to the point of prompting my dad to once ask me—when my gregariousness around my American social circles contrasted with the antisocial disposition I maintained around my family—if I was racist against my own kind. It’s in response to that distance that I, years later, created my own home movie in an effort to connect to family. ‘Mexicanamerican’ is an impressionistic, found-footage collage interrogating the sacrifices that accompany the American Dream, culture’s effect on our identities, and the world as my parents saw it.

That alienation worsened to the point of prompting my dad to once ask me—when my gregariousness around my American social circles contrasted with the antisocial disposition I maintained around my family—if I was racist against my own kind. It’s in response to that distance that I, years later, created my own home movie in an effort to connect to family. ‘Mexicanamerican’ is an impressionistic, found-footage collage interrogating the sacrifices that accompany the American Dream, culture’s effect on our identities, and the world as my parents saw it.

ARTISTIC STATEMENT

‘Mexicanamerican’ weaves together decades-old VHS home video footage with modern-day interviews of my parents, Lalo and Beby, and my younger brother, Edgar, to tell the story of how my family integrated itself within the United States. Originally, it was conceived alongside my youngest brother, Eben, as a short-subject talking-head documentary—a more direct nod to its namesake, Martin Scorsese’s ‘Italianamerican.’ But the discovery of my parents’ analog video archive inspired a total reimagining of the film as a feature-length found-footage collage, narrated by those same interviews as voice-over.

My connection to this film is personal and lifelong. This documentary is, at its heart, a tribute to my parents—an expression of love and gratitude for who they are, the values they carry, the conditions that shaped them, and the sacrifices they made when they crossed the border in search of a better life for my two brothers and me. It’s a way of not only honoring the physical journey they undertook and the weight they carried in doing so, but also of letting others in on the joy of knowing their humor, charm, resilience, and disarming thoughtfulness.

The story is told almost entirely from their perspective—in their own words and through archival footage they themselves recorded over the years. That perspective grounds the film in the lived experience of two working-class immigrants from rural Mexico, and my role as their son shapes how I’ve chosen to present that experience: not as a sweeping, generalized account of immigration, but as an intimate, memory-driven portrait of two people I adore and look up to.

At the same time, this project is also a personal reckoning. As a thoroughly assimilated first-generation American, I spent much of my early life distancing myself from my cultural roots, often unconsciously, in favor of the mainstream. In writing, directing, and editing this film, I’ve tried to revisit and repair what I once perceived as a failure to fully embrace my Mexican heritage. The creative decisions I made—what I chose to linger on, to include, to omit—were all motivated by that pursuit. In that way, the film reflects not just my parents’ journey, but also my own: a return, a reflection, and a reconnection.

Bios

Eddie Sánchez (Director/Producer/Editor/

Eben Sánchez (Co-Director) is a filmmaker from Portland, Oregon currently completing his senior year as a Media Studies major and Religious Studies minor at Pomona College. Eben most recently premiered his debut short as a writer-director, DULCE COMPAÑÍA, centered around a young poet who overcomes self-hatred and shame about his sexuality by confronting his family’s intergenerational trauma.

Michael Rogerson (Producer) is a Brooklyn based producer and director of film and theatre, and the artistic director of Silencio Projects. With Silencio, he produced the US premiere of Simon Longman’s Gundog (co-produced by CultureLab LIC), the Midwest premiere of Christopher Chen’s Home Invasion, and Midwest premiere of Marius von Mayenburg’s The Dog, the Night, and the Knife (in partnership with Fulton Street Collective), and a basement-rock-show version of Enda Walsh’s Disco Pigs, which played multiple sold out runs in real DIY venues in Logan Square. His short film All the Way Down This Time played at Queens International Film Festival and won best short at Queer Fear Film Festival. He recently assisted Les Waters on Grief Camp at Atlantic Theater Company, and is currently developing a reduced cast adaptation of Peter Weiss’ The Investigation. He graduated from Northwestern University, and trained with Anne Bogart’s SITI Company.

Justin Enoch (Sound Designer/Mixer) is a Romanian-born, LA-based sound designer, composer, and interdisciplinary artist. Their work has screened at Sundance, TIFF, and the Student Academy Awards. Their most recent credits include TAHARA (sound design, foley), AGAINST REALITY (sound design, mix), FLAIL (sound design, composer), and INSIDE THE RED SEA MISSION (composer).

Nudo (Composer) is a regional-electronic duo based in Texas formed by Eric Hernandez and Joaquin Tenorio. “Nudo incorporates samples, field recordings, and electronics in service of a sound that captures the textures of the Texican landscape they know so intimately—the joy and the strife; the desert calm and the looming conflict.” (Nina Protocol).

ALL DONATIONS ARE TAX-DEDUCTIBLE